By: Julia Lloyd and Angela McLean

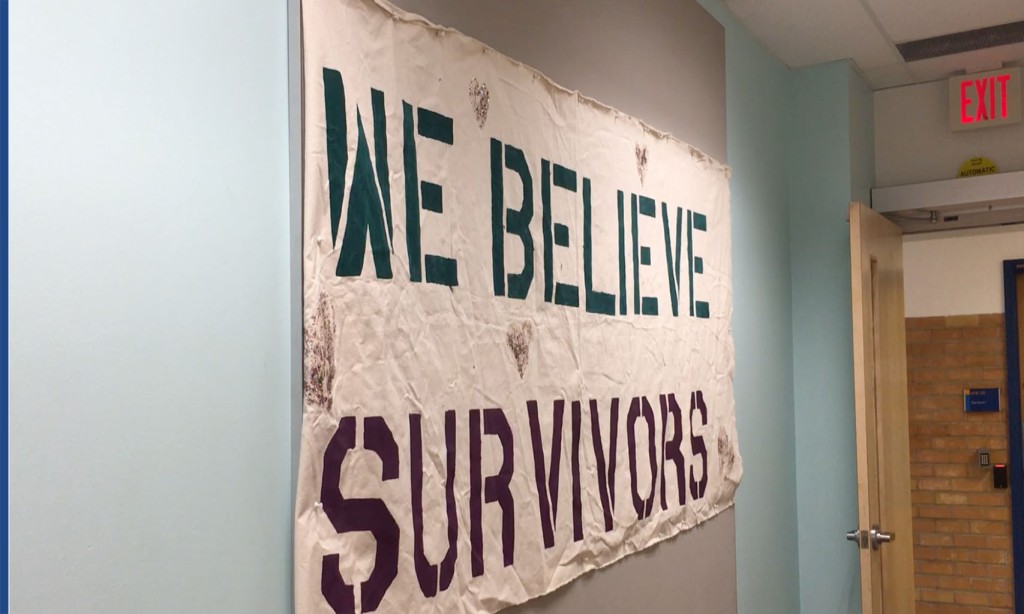

(Photo courtesy of Angela McLean)

Canadian actresses Sarah Polley and Larissa Gomes are just two of many women who have brought forward allegations of sexual harassment and assault at the hands of now-infamous producer Harvey Weinstein. But A-list stars are not the only ones sharing their stories.

Hundreds of thousands of people worldwide have been using #MeToo on social media this week to name themselves as survivors of sexual harassment or assault, but some Ryerson experts and students have concerns about the hashtag’s effectiveness and messaging.

The #MeToo movement was originally started by activist Tarana Burke 10 years ago. She created it as a way for women of colour to share experiences of sexual violence and connect with each other.

On Sunday, Oct. 15, American actress Alyssa Milano reinvented the movement, tweeting, “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet.” She included a screenshot of a text note from a friend saying the postings “might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.”

Milano’s post received over 60,000 responses.

“[This] is a really good way to raise awareness of what is happening in the world right now,” said Jade West, the director of administration for Ryerson’s Students for Mental Awareness, Support and Health group. “With everything going on with Harvey Weinstein in the news, I think it is as important a time as any to speak up and show [the scale of this and] that it is not OK.”

However, not all feedback to the current movement has been positive.

“While it’s bringing attention to the amount of people who have experienced sexual assault, I don’t see how it’s changing the way people look at sexual assault,” said Lauren Dunlap Sciacchitano, a first-year medical physics student. “No one is having a conversation about how dancing closely with someone at the club is still seen as an invitation to be fondled or all the ‘creepy’ behaviour that results in people being coerced into sexual activities that they didn’t consent to or didn’t want to consent to.”

Farrah Khan, a co-ordinator at Ryerson’s office of sexual violence support and education, says she agrees that the movement’s messaging missed the mark.

“We’re not asking for the community to have a conversation about when they don’t intervene, when they don’t say anything, when we see something and we go, you know what, somebody else will deal with it, or we’re like, oh that’s just the way he is or that’s just the way that she talks to people,” Khan said.

“We’re not having that conversation and I think that’s what’s important here.”

On Sunday, Khan took to her personal Twitter with her own expression of #MeToo. But she also added, “Would love if #MeToo compelled people who commit sexual violence to own up to their actions and not survivors having to tell our stories.” The tweet has over 1,000 likes.

One of the groups excluded from the conversation are the perpetrators and supporters of sexual violence. Days after the movement went viral, some of these people chimed in with their own social media hashtags – #ididit, #ivedoneit and #itwasme.

This was just one of the ways they responded. Khan said after posting about #MeToo, she received messages from men she knew in her 20s that had supported the perpetrator over her, apologizing for their behaviour.

“I think it’s a first step,” Khan said. “I think we aren’t yet at a place in Canada or in the world where we can have honest conversations about the fact that we know and love people who may have committed harm against folks, or we ourselves have, and we have to have those tough conversations.

“I don’t think you get a pat on the back for that; what you do get is hey, our community’s going to hold you accountable now and that means I’m going to be a part of the conversation of what it means for you to actually support folks.”

Martese Belle, a third-year English student, said she has experienced sexual harassment and participated in the movement.

“As much as I think hashtags are stupid and social media won’t change the world, this movement isn’t about that,” said Belle. “It’s about us as women and men and anyone who has been victimized coming together and saying we’ve had enough and something needs to change. We need to be taken seriously.”

Despite all the buzz and constant mentions on social media, Yamikani Msosa, a co-ordinator at the Office of Sexual Violence Support and Education, emphasized that survivors should not feel pressured to participate.

“These campaigns are amazing outlets for folks who want to participate in them, [but] they can also be triggering for other folks,” Msosa said. “If we look at the concept of consent, consent is disclosure. The right to not participate doesn’t make your experiences any less valid.”

Msosa said taking social media breaks and finding outlets for self-care and self-love that work for you are appropriate ways of responding.

People can also “turn their experience into a positive thing that will make them stronger,” said West. “Yes, it happened, however that doesn’t mean you have to let it have power over you still. It’s all about your mindset and instead of saying ‘I’m broken’ say ‘I’m growing and healing.’”

Leave a comment